ZFS dRAID Primer

10 minute read.

Introduced in OpenZFS version 2.1.0 and initially supported in TrueNAS 23.10 (Cobia), declustered RAID (dRAID) is an alternate method for creating OpenZFS data virtual devices (vdevs).

Intended for storage arrays with numerous attached disks (>100), the primary benefit of a dRAID vdev layout is to reduce resilver times. It does this by building the dRAID vdev from multiple internal raid groups that have their own data and parity devices, using precomputed permutation maps for the rebuild IO, and using a fixed stripe width that fills storage capacity with zeroes when necessary.

Depending on data block size and compression requirements, a dRAID pool could have significantly less total storage, especially in situations where large numbers of small data blocks are being stored.

Due to concerns with storage efficiency, dRAID vdev layouts are only recommended in very specific situations where the TrueNAS storage array has numerous (>100) attached disks that are expected to fail frequently and the array is storing large data blocks. If deploying on SSDs, dRAID can be a viable option for high-performance large-block workloads, such as video production and some HPC storage, but test the configuration thoroughly before putting it into production.

Current investigations between dRAID and RAIDz vdev layouts find that RAIDZ layouts store data more efficiently in all general use case scenarios and especially where small blocks of data are being stored. dRAID is not suited to applications with primarily small-block data reads and writes, such as VMware and databases that are better suited to mirror and RAIDz vdevs.

In general, consider dRAID where having greatly-reduced resilver time and returning pools to a healthy state faster is needed. The implementation of dRAID is very new and has not been tested to the same extent as RAIDZ. If your storage project cannot tolerate risk, consider waiting until dRAID becomes more well-established and widely tested.

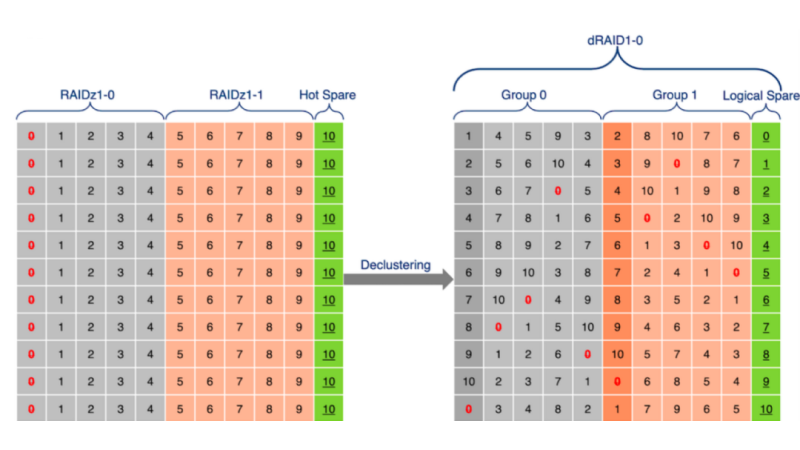

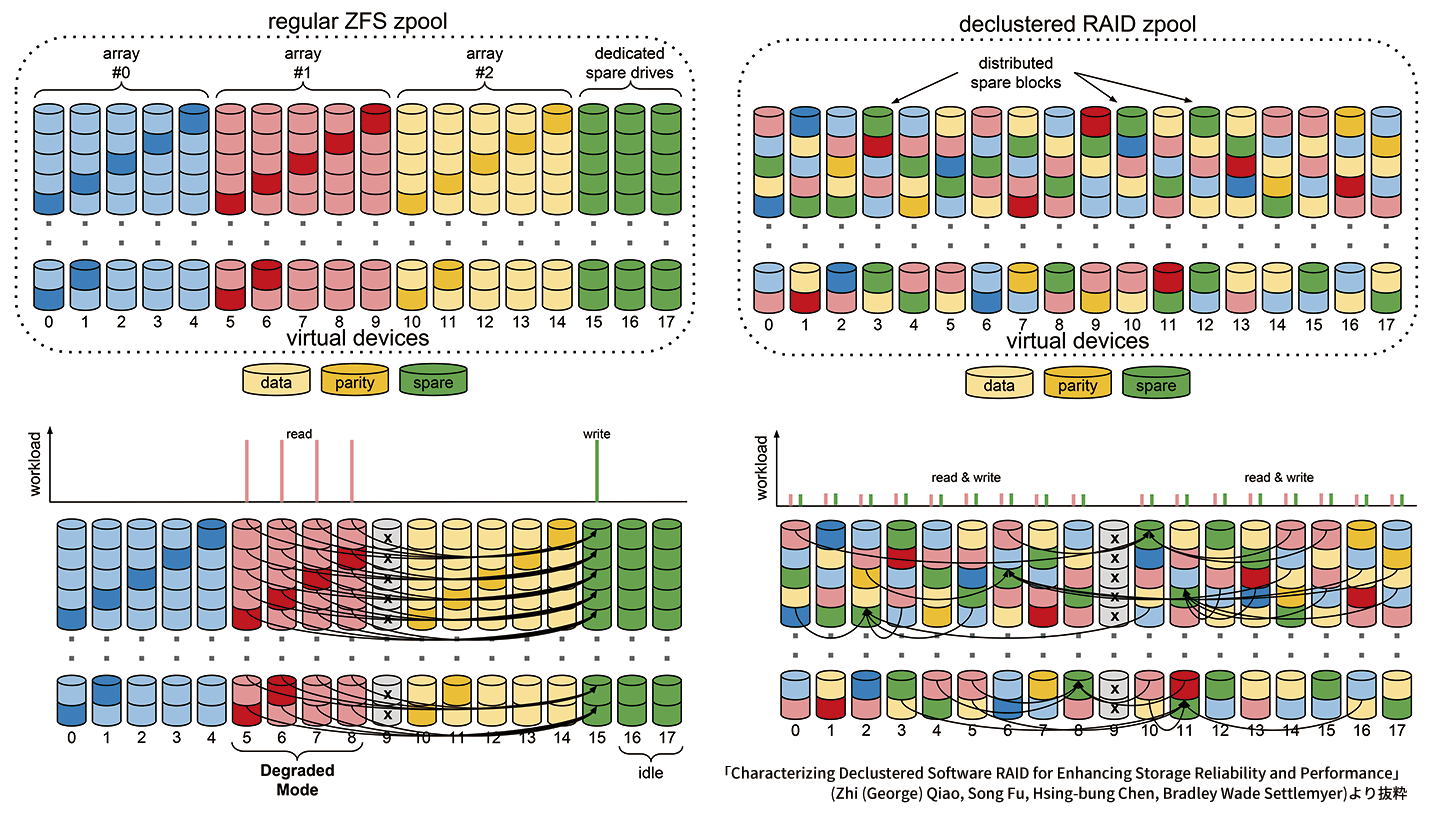

These images demonstrate the differences between dRAID and RAIDz layouts in OpenZFS:

Stripe width is fixed in dRAID, with zeroes added as padding. This can have a significant effect on usable capacity, depending on the data stored.

In a redundancy group of eight data disks using 4k sector disks, the minimum allocation size is 32k. Any files smaller than 32k still fill an entire stripe, with zeroes appended to the write to fill the entire stripe. This greatly reduces the pool usable capacity when the pool stores large numbers of small files.

dRAID vdevs typically benefit greatly from larger record sizes and have some hard limitations on dataset and zvol record sizes. The absolute minimum dataset record size is 128k and zvol record size is 64k to 128k for zvols. However, this does not account for typical data access patterns.

When datasets are expected to have a heavy sequential I/O pattern, a 1MB record size can be beneficial for compression. However, datasets, and typically zvols, are expected to have heavy random I/O patterns, it is recommended to remain closer to the minimum 128k (or 64k for zvols) record size. Selecting a record/block size smaller than the minimum allocation size is catastrophic for pool capacity.

dRAID uses an array of predetermined permutation maps to determine where data, parity, and spare capacity reside across the pool. This ensures that during resilvers, all IO (reads and writes) distribute evenly across all disks, reducing the load on any one disk.

Because a permutation map automatically selects during pool creation, distributed spares cannot be added after pool creation. If adding spares after pool creation is a critical requirement, create the pool using a RAIDz layout.

dRAID uses a different methodology from RAIDz to provide hot spare capacity to the data vdev. Distributed hot spares are allocated as blocks on each disk in the pool. This means that hot spares must be allocated during vdev creation, cannot be modified later, and that every disk added to the vdev is active within the storage pool.

Disk failure results in the dRAID vdev copying the parity and data blocks onto the spare blocks in each fixed stripe width disk. Because of this behavior and inability to add distributed hot spares later, it is recommended to always create a dRAID vdev with at least one or more distributed hot spares and to take additional care to replace failed drives as soon as possible.

This is a new resilver type used by dRAID where blocks are read and restored sequentially. This greatly increases resilver operation speed as it does not require block tree traversal.

Sequential resilver is made possible by the use of fixed stripe width in dRAID. During a sequential resilver data is read from all pool members.

Checksums are not validated during a sequential resilver. However, a scrub begins after the sequential resilver finishes and verifies data checksums.

This process occurs after a disk failure results in a distributed hot spare replacing a failed drive. This is essentially a resilver, but data redistributes across the pool to meet the original distributed configuration.

During rebalancing, a traditional resilver is performed as the pool is not in a degraded state. Checksums are also verified during this process.

The traditional ZFS resilver. The entire block tree is scanned and traversed. Checksums are verified during the repair process. This can be a slow process as it results in a largely random workload that is not ideal for performance. In a RAIDz deployment this also puts extra strain on the remaining disks in the vdev, as they are all being read from simultaneously.

The terminology used for a dRAID layout is similar to that used for RAIDz, but could have a different meaning. We recommend reviewing this list of terms and definitions before attempting to create storage pools with a dRAID layout in TrueNAS.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Children (C) | Number of drives included in the dRAID deployment. |

| Data Devices (D) | Number of data devices in a redundancy group. This number can be quite high, but generally a lower number results in greater performances and capacity is more effectively used. |

| Distributed hot spare (S) | Unlike in a RAIDz configuration where spares remain inactive until needed, in a dRAID configuration spare capacity is distributed across the drives. This results in all drives being active members of the pool. This number cannot change after pool creation. |

| Parity Level (P) | Distributed parity level of a dRAID redundancy group. This ranges from 1 to 3 and is similar to the RAIDz parity level. |

| Redundancy group | dRAID layouts use equivalent RAIDz vdevs as the foundation for the complete dRAID vdev. A redundancy group is composed of parity devices and data devices. Redundancy group size impacts storage performance and capacity. |

| Vdev | An OpenZFS virtual device. dRAID layouts allow much larger vdevs. 100+ device vdevs are not uncommon. Distributed hot spares are shared across all redundancy groups in a vdev. |

A single dRAID vdev can have multiple redundancy groups, just as a RAIDz can have multiple vdevs. A dRAID redundancy group is roughly the equivalent of a RAIDz vdev. dRAID redundancy groups can be much wider than RAIDz vdevs and still have the same level of redundancy. dRAID variables in estimating layouts are:

- Parity (P) in each redundancy group

- Data disks (D) in each redundancy group

- Spares (S)

- Total number of drives, children (C), in the dRAID vdev

When configuring dRAID layouts consider the given number of disks and compare the capacity of those disks laid out in RAIDz and dRAID configurations. The ZFS Capacity Calculator and ZFS Capacity Graph allow you to make the comparison.

TrueNAS uses this formula to estimate the total capacity of a dRAID data vdev:

\(Capacity = (C - S) \cdot \left(\frac{D}{{D + P}}\right) \cdot DS\)Where:

- C is the children number (total number of drives in the layout).

- S is the distributed hot spare number.

- D is the data device number in the redundancy group.

- P is the parity level in the redundancy group.

- DS is the minimum disk size common to all disks in the vdev.

For example, setting up a single dRAID1 vdev layout with matching 1.82 TiB disks, 8 data devices, 1 distributed hot spare, and 10 children results in an estimated 14.58 TiB (rounded) total capacity:

\((10 - 1) \cdot \left(\frac{8}{{8 + 1}}\right) \cdot 1.82 = 9 \cdot 0.89 \cdot 1.82 = 14.5782\)This formula does not account for additional metadata reservations, so the total estimated capacity is likely to be slightly lower.

See how dRAID lays out and shuffles data. Specify any valid dRAID layout and see it both in a pre-shuffled and a post-shuffled state.

draid : d : c : s Enter dRAID vdev parameters above

| # Disk # Parity # Data # Spare # Slice |

ZFS allows groups to span multiple rows, which means it does not require each row to contain a whole number of redundancy groups. This layout has several advantages over requiring whole groups in each row:

- Group count - Group count is not a relevant parameter when defining a dRAID layout. ZFS only needs the group width and all groups will have the desired size.

- Group widths - ZFS can support all possible group widths (greater than or equal to the physical disk count).

ZFS determines the number of groups by the least common multiple (LCM) of the group width (D+P) and the number of physical drives minus spares (C-S). The logic within dRAID is simplified when the group width is the same for all groups, although some aspects, such as computing permutation numbers and drive offsets, are more complex. This flexible layout ensures even distribution of data and parity while maintaining high performance and resilvering efficiency.

See vdev_draid.c for more information.

dRAID layouts require more testing before we make layout recommendations on the number of spares or parity levels. When using dRAID, consider these factors:

dRAID does not support partial-stripe writes.

Small-block writes to dRAID vdev are padded with zeros to span a redundancy group, which creates a lot of wasted space. Include special allocations class vdevs (i.e., L2ARCs, SLOGs, and metadata) in a dRAID layout to handle this type of IO.

You cannot add virtual spares after creating the vdev because spare disks are distributed into the dRAID vdev.

dRAID performance should match that of an equivalent RAIDz pool. Vdev IOPS scale based on the quantity of redundancy groups per row and throughput scales based on the quantity of data disks per row.

If creating a dRAID pool with more than 255 disks, you need to use multiple vdevs with fewer disks rather than one vdev with the maximum number of 255. Adhering to best practices means keeping all vdevs alike. So rather than taking 300 disks and creating one 255-wide vdev and one 45-wide vdev, use two 150-wide or three 100-wide vdevs to improve performance and redundancy.

Use dRAID redundancy groups with similar numbers of drives and parity levels as in RAIDz vdevs.

dRAID pool expansion requires the addition of one or more new vdevs, just as with RAIDz. Because dRAID could have 100 or more disks in it, the best practice of using homogeneous vdevs in a pool still applies, which means expansion increments to dRAID-based pools can be very large.

These resources go much further in-depth with dRAID concepts and usage details: